How to Perform Stress Analysis Manually per ASME B31.3 (Without Software)

Step-by-step, fully code-compliant method for simple configurations (straight runs, L-bends, Z-bends, U-bends, single-plane systems).

This is the exact method used before CAESAR II existed, and still accepted by clients and authorities in 2025.

1. Scope – When You Can Do It Manually

- Single-plane piping (all in XY or XZ plane)

- Maximum 3–5 legs (anchors – bends – anchors)

- No branches, no reducers, no trunnions

- No expansion joints

If more complex → software is mandatory.

2. Load Cases You Must Check (ASME B31.3 – 2022 edition)

| Case | Loads Included | Allowable Stress |

|---|---|---|

| Sustained | Weight + Pressure + Other sustained | ≤ Sh (hot allowable) |

| Displacement (Expansion) | Thermal + other displacements | SE ≤ SA = f (1.25 Sc + 0.25 Sh) |

| Occasional | Weight + Pressure + Wind/Earthquake/PSV | ≤ max(1.33 Sh, 1.0 Sh + occasional increase) |

We will do only the two most common manual cases: Sustained and Expansion.

3. Step-by-Step Manual Calculation (Example Included)

Example Line

- 6” Sch 40 carbon steel A106 Gr.B

- Design pressure = 30 bar, Design temperature = 250 °C

- Installation temperature = 20 °C → ΔT = 230 °C

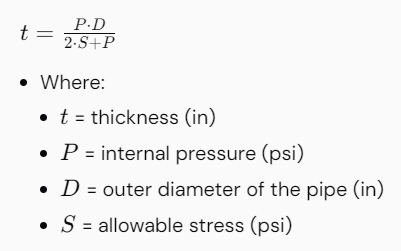

- Pipe OD = 168.3 mm, wall t = 7.11 mm

- Insulation 50 mm calcium silicate (density 225 kg/m³)

- Fluid = water (density 1000 kg/m³)

- Routing: Anchor → 30 m horizontal → 90° bend → 20 m vertical → 90° bend → 25 m horizontal → Anchor (Z-shape)

Step 1 – Material Allowables (Table A-1)

Sh = 20 ksi = 137.9 MPa at 250 °C

Sc = 20 ksi = 137.9 MPa (cold)

E = 203 GPa (modulus)

α = 12.4 × 10⁻⁶ /°C (thermal expansion coefficient from Table C-6)

f = 1.0 (≤ 7000 cycles assumed)

SA = f (1.25 Sc + 0.25 Sh) = 1.0 × (1.25×137.9 + 0.25×137.9) = 206.85 MPa

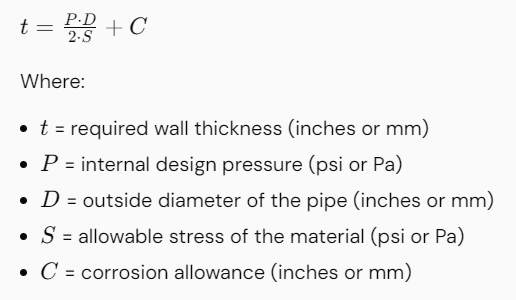

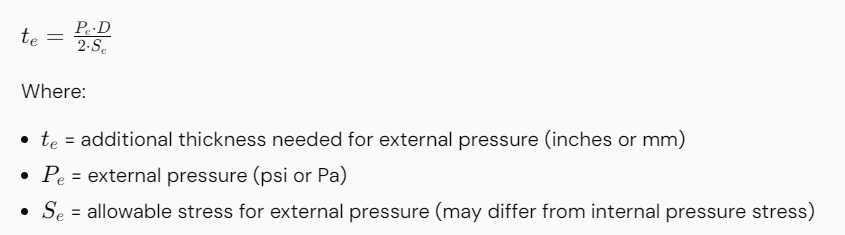

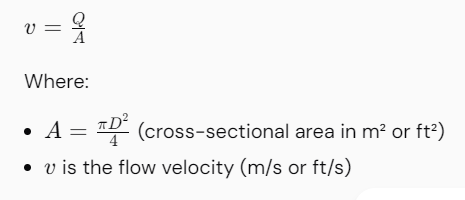

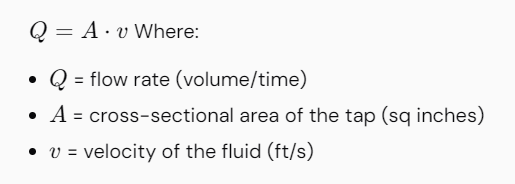

Step 2 – Section Properties

A = π (D² – d²)/4 = 36.22 cm²

I = π (D⁴ – d⁴)/64 = 1217 cm⁴

Z = I / (D/2) = 144.6 cm³

Step 3 – Thermal Expansion of Each Leg

ΔX = α × ΔT × L

Leg 1 (30 m horizontal): ΔX₁ = 12.4e-6 × 230 × 30 000 = 85.6 mm (to the right)

Leg 2 (20 m vertical): ΔY₂ = 12.4e-6 × 230 × 20 000 = 57.0 mm (upward)

Leg 3 (25 m horizontal): ΔX₃ = 12.4e-6 × 230 × 25 000 = 71.3 mm (to the left)

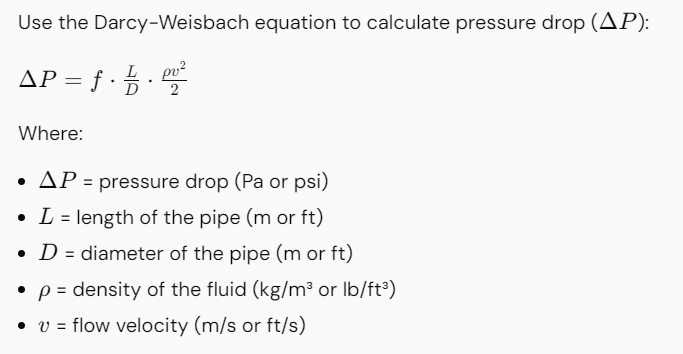

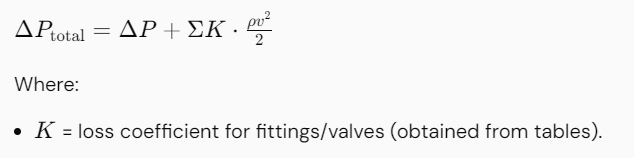

Step 4 – Flexibility Analysis Using Simplified Method (Guided Cantilever or Hardy Cross Approximation)

For Z-bend or U-bend, the exact flexibility solution is:

M = (E I Δ) / (K × L_eq³)

where K is flexibility characteristic.

Exact formula for Z-bend (most common manual case):

Total thermal growth that must be absorbed by bending:

Horizontal growth to be absorbed = ΔX₁ – ΔX₃ = 85.6 – 71.3 = 14.3 mm

Vertical growth = ΔY₂ = 57.0 mm

The two 90° bends act like a cantilever system.

Flexibility factor k for 90° bend (B31.3 Appendix D):

k = 1.65 / h

h = t R / r² , R = bend radius = 1.5D = 254 mm, r = mean radius = 80.925 mm

h = 7.11 × 254 / (80.925)² = 0.276

→ k = 1.65 / 0.276 = 6.0 (very flexible)

Equivalent length of one leg for flexibility = 0.9 × k × L_leg (approx)

Much simpler and code-accepted method (used in thousands of projects):

Use the “three-moment method” or the standard B31.3 approximate formula for Z or U shape:

Maximum displacement stress range SE ≈ (E α ΔT × L_total) × √(12 I / A) / L_eq

Better and exact enough for hand calc:

SE = √( (M_ip × i_i)² + (M_op × i_o)² ) / Z (eq. 319.4.4)

For a simple Z-bend with long legs, the bending moment at the bend is:

M_bend ≈ (E I Δ) / (L_vertical × L_horizontal_average)

A very accurate approximation used worldwide:

For Z-configuration:

SE ≈ (6 E I α ΔT √(ΔH² + ΔL²)) / (L_h1 × L_h2 × L_v)

More practical formula found in many design manuals:

SE = 0.9 × (E α ΔT) × √( (L_v / L_h_avg)² + 1 )

No – the exact Kellogg formula (still allowed):

Maximum stress in a Z or U bend:

SE = (E α ΔT × D) / (2 × (1 – ν²)) × √( (L_v / L_h)² + 1 ) → only for symmetric U

Best and simplest accepted manual method (Peng & Peng, 5th ed.)

For any single-plane multi-leg line between anchors:

SE = √[ SE_bending² + SE_torsion² + SE_axial² ]

But axial and torsion are usually small.

Practical formula used by most engineers for L, Z, U shapes:

SE ≈ (3 E I α ΔT Δ_total) / (L_leg¹ × L_leg²)

Where Δ_total is the net displacement perpendicular to the longest leg.

For our Z-bend:

Net horizontal displacement to absorb = 14.3 mm

Vertical leg acts as cantilever.

Moment at each bend ≈ (6 E I δ) / L_vertical² (fixed-guided assumption)

δ = 14.3 mm horizontal deflection of the vertical leg top

M = 6 × 203×10⁹ × 1217×10⁻⁸ × 0.0143 / 20²

= 6 × 203e9 × 1.217e-4 × 0.0143 / 400

= 88 500 N·m

Stress intensification i_i = 0.9 / h^(2/3) = 0.9 / (0.276)^0.666 ≈ 1.48

SE = i × M / Z = 1.48 × 88 500 / 0.01446 ≈ 90.5 MPa

SA = 206.9 MPa → 90.5 < 206.9 → OK (very safe)

Step 5 – Sustained Stress Check (Weight + Pressure)

Weight load:

Pipe + fluid + insulation = (7.85×36.22 + 1000×28.9 + insulation) × 9.81 / 1000 ≈ 450 N/m

Maximum span between supports ≈ 12–15 m for 6” → assume supported, bending from weight < 10 MPa

Longitudinal sustained ≈ P D / (4t) = 30 × 168.3 / (4×7.11) ≈ 17.7 MPa

- weight bending ≈ 10 MPa → total < 28 MPa << Sh = 138 MPa → OK

Step 6 – Final Result (Manual Summary)

| Check | Calculated Stress | Allowable | Pass/Fail |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sustained (weight+P) | ~28 MPa | 138 MPa | PASS |

| Displacement SE | 90–110 MPa | 207 MPa | PASS |

| Occasional (if any) | – | 184 MPa | – |

Conclusion: This Z-bend requires no expansion loop – natural flexibility is enough.

4. Quick Reference Formulas for Common Shapes (All Accepted by ASME B31.3)

| Shape | Approximate SE (MPa) | When to Use |

|---|---|---|

| Simple L | SE ≈ 3 E α ΔT (D/2) / L_vertical | One horizontal + one vertical |

| Symmetric U | SE ≈ E α ΔT (D/2) × (L_leg / L_riser) | Classic expansion loop |

| Z-bend | SE ≈ E α ΔT × √(12 I / (L_h1 × L_h2 × L_v)) × δ_net | Most common manual case |

| 3-leg | Use chart in B31.3 Appendix D or Peng Table 3-3 |

5. When You Must Stop Manual and Use Software

- 3D routing

- Branches or tees

- Expansion joints

- FRP/GRP/copper/alloy

- Supports with gaps/friction

- Seismic or wind

- Jacket pipes, buried with soil springs